Inmates in the East Hall of the South Dakota State Penitentiary on July 8, 2025. (Courtesy of South Dakota Department of Corrections)

SIOUX FALLS — The scene was surreal from the jump.

There we were, a gang of eight reporters scrunched together in the claustrophobic lobby of the state penitentiary, waiting for a sales pitch on a product sold the day before to customers who were never us anyway.

The state’s Project Prison Reset task force had already voted to build a new prison on the eastern edge of the city that’s played host to “The Hill” since before statehood.

That group’s membership had toured the labyrinthine quartzite monolith that houses around 800 prisoners months ago.

We already knew the forthcoming message: This hill is no shining city. It’s a terrible, awful, no good, very bad place, unsafe for inmates and correctional officers alike.

Old hat, new cattle

Aside from an exclusive tour offered to KELO-TV earlier this year, the Department of Corrections has kept reporters out of the pen for the three-year duration of the new prison debate.

That’s partly why I showed up Wednesday with a unique perspective among our gang of eight. I was the only one who’d toured the building before. I’d been there plenty as an Argus Leader reporter. It used to be normal to visit the warden in their office, inmates in the visit room, or staff in their work environment, be that out on the floor or inside the prison industries building. I also witnessed an execution back in 2012.

I had at least some idea of what we were in for.

On Wednesday morning, though, spokesman Michael Winder assured me I’d see more than I ever had before, and much of what had changed in the decade since I’d last darkened the pen’s reinforced doors.

This tour, he explained, would be the first to take us onto the catwalks where inmates live. We’d also see the communal shower downstairs, where 60 men bathe at once as another 60 wait outside on benches, and walk through the underground tunnel that leads to the indoor recreation area.

That expanded access was among the reasons we weren’t allowed to bring cameras. Inmates have the right not to be photographed, Winder said — they don’t like to feel like animals in a zoo — and it would be impractical for him to police eight shutterbugs simultaneously.

He’d take pictures for us, we were assured. The reason for saying no to audio recording or the use of our own notebooks never was fully explained.

Briefing: There will be catcalling

Some changes were apparent right away. We’d all need to pass through a metal detector, shoehorned into place in 2022 to create the pre-tour waiting zone’s aforementioned cramped conditions.

First, we were taken upstairs for a security briefing and introductions with the eight people who’d accompany us. We’d need to stick together and keep moving, Corrections Secretary Kellie Wasko told us. The men would stand at the front and back of our single-file line, Wasko explained, because inmates are less likely to catcall if a man stands between them and their target.

There would be catcalling, she promised.

We could see in through the barred second door of our first doubled-doored security checkpoint as we huddled and exchanged our driver’s licenses to Maj. Cody Hanson for visitor’s badges.

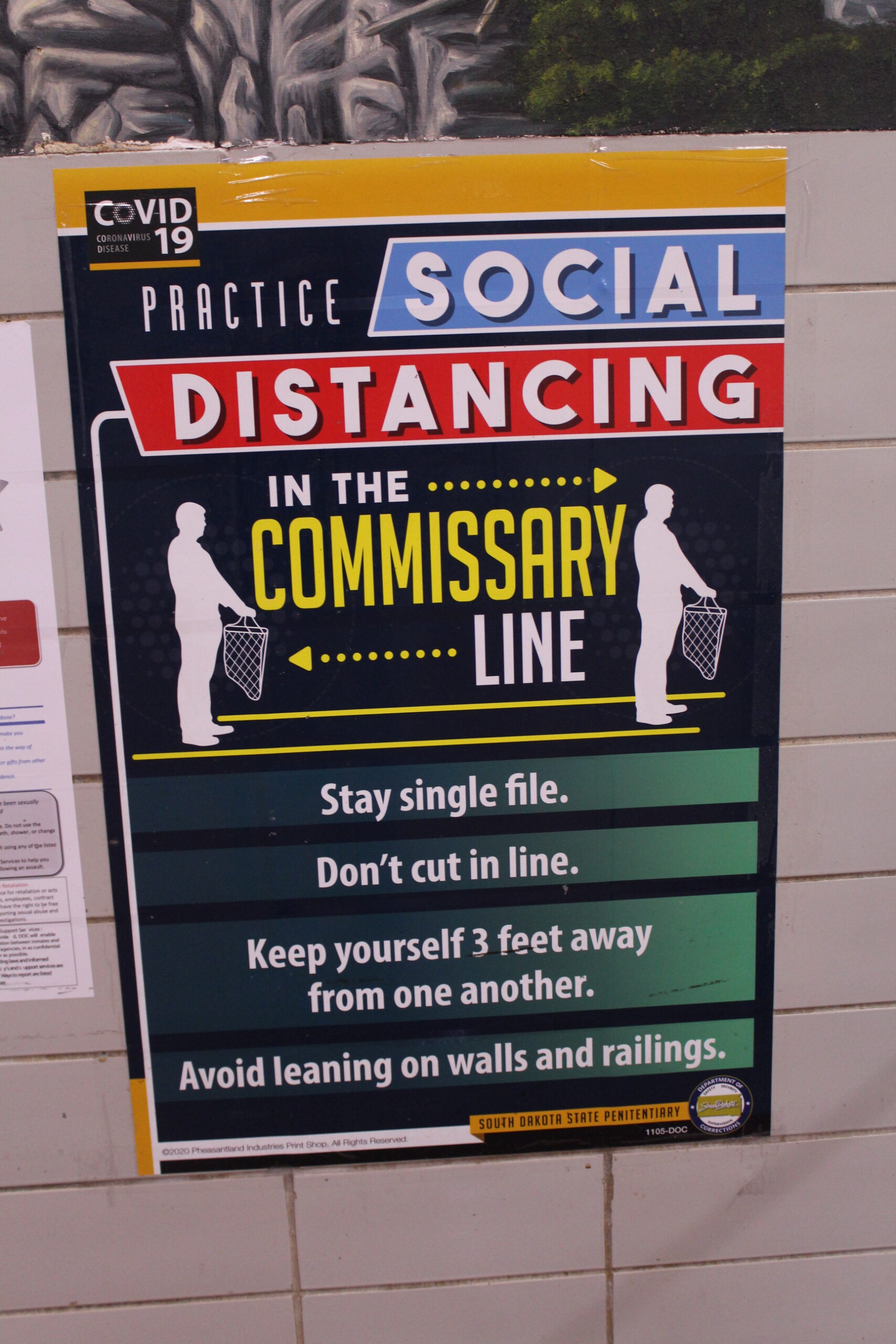

That’s when I noticed the next new thing: A COVID-era poster asking inmates to queue 3 feet apart in the pickup line for commissary, otherwise known as the prison store.

Some things hadn’t changed. The first five inmate faces I saw belonged to black and Native American men, a reminder that South Dakota, like the U.S. as a whole, locks up people of color at higher rates than white folks.

First impressions: Pooled water and cusses

Between inmate drug overdoses, gang fights and security lockdowns, things have been pretty messy in state prisons lately. Wasko has come under no small amount of scrutiny as a result. It was no surprise to hear Winder tell us that two inmates had scuffled in the chow hall shortly before our tour (neither was seriously injured, he’d tell me the next day).

Once inside, we saw a less metaphorical mess. A pool of water spread across the floor from a cell in federal hall, the 170-bed midsection between East Hall and West Hall, the prison’s two linear, five-floor wings.

“We had a backup,” said a smiling Amber Pirraglia, the director of prisons.

Our group had to step around the toilet water puddle on its way to East Hall, a dance soundtracked by profane chants leveled by inmates at Wasko.

“This is just normal,” when she shows up, Wasko said, but “they’re pretty fired up.”

We hurried to one side of the hall, walking by rows of barred cells. Each floor of the five in East Hall has 20 cells on either side, each a home for two inmates in a space designed to hold one back in 1881.

Wasko doesn’t like bars, she said. Inmates can spit through bars. They can throw urine. She prefers solid doors with windows and closable food ports.

She also doesn’t like the size of the cells. Modern standards expect each inmate to have 35 square feet of “unencumbered space,” she told us. Inmates on the Hill split 56 total. That’s four less than my master bathroom at home, minus our closet space. I can barely squeeze by the bathtub to get to that closet when my 7-year-old’s brushing her teeth.

In the cells that weren’t blocked by hung T-shirts, I saw flip-flops tied to walls, paper trash bags stuffed between bars at the top of cells, and books and bags of chips and toiletries stuffed into every corner.

‘They’re too fired up’

It was hot. The air conditioning is wildly inefficient. It felt like 80 degrees.

“What air conditioning?” the Department of Correction’s inspector general said.

If you’re wondering what 400 people stuffed in a hot box with 200 toilets smell like at 80 feels-like degrees, you’ve wondered enough to know why the smoke we saw as we climbed the steps to the catwalk was an alarming sign but a welcome aroma.

“Something is on fire,” I wrote in my penitentiary-issue pocket notebook. “Can see the smoke.”

Inmates can start blazes by shoving toilet paper into electrical outlets, we were told.

Wasko wanted us on the narrow metal staircases so we could know what it’s like for the officers as they deliver food, mail and medicine, respond to fights on the catwalks or haul empty stretchers up and injured inmates down.

On the way up, we walked past two “fishing lines,” one of which had something tied to the end. They appeared to be fashioned out of T-shirts or bits of bed sheet. That’s how inmates deliver small bits of contraband from one tier to the next, Wasko told us.

At the top of the stairs, Wasko decided we weren’t going to walk across the fifth floor tier after all.

“They’re too fired up.”

Showers: Stabbings and steamed cameras

Next, we visited the showers below East Hall — and revisited that toilet backup.

One officer has to supervise the showers downstairs while another monitors a video feed. Every few feet in the entryway to the giant communal shower stall, we saw large tile columns — “prime locations” for injuries, Wasko said, as inmates can stay out of an officer’s sight line and strike or stab their targets.

Steam clouds the cameras on the opposite wall pretty quickly during shower time, Maj. Hanson said.

Modern prisons have showers in every “pod,” the circular cell configuration used in newer facilities, Wasko said. It’s typically one for every 12 inmates, she said, meaning fewer people for officers to watch and fewer opportunities for assaults or contraband passage.

“They can shower whenever they want to,” she said of inmates in modern facilities, with curtains covering men at the midsection, and women at the chest and midsection.

As Wasko spoke, water from the still-pooling toilet backup in the federal hall cell splashed from above to the floor below the stairway.

Pirraglia mopped it up.

Another waterfall fell in a sheet about a minute later. Pirraglia laughed. She left the mop against the wall.

50-cent video visits

From the showers, we walked through the white-walled underground tunnel that leads to the indoor recreation area.

A tour guide pointed to the hallway’s wall phones. That’s where inmates call out from when they can’t call from their prison-issue electronic tablets.

We also saw a video visit kiosk in that same hallway, the first in a set of what will be 17. The others, located in a separate room, are set to go live on Monday.

The operational kiosk’s screen already had a spiderweb crack.

The kiosks are part of a video-only visit setup launched recently in response to the alleged passage of contraband during in-person visits. Some family members of inmates have complained on social media and to people like me about this.

The price paid by inmates for the video calls that replace the free in-person visits is 50 cents a minute.

Pheasantland: Like Amazon, sort of

From there, it was Pheasantland Industries. One building houses the license plate, print and carpentry shops, as well as the space rented by Hope Haven Ministries, a nonprofit that distributes wheelchairs to the needy with the aid of inmate labor.

On the days they work, anyway. No one was working when we showed up.

The shops looked much the same as before, with one major difference: There are now locked toolboxes with designated spots for every tool, installed as a preventative measure against the theft of potentially lethal weapons.

Wasko seemed especially proud to show off the big metal warehouse now home to the commissary program and its inventory.

Inmates fluttered about between rows of shelving stacked with boxes of nacho chips, sodas, cookies and various other off-brand versions of consumer goods. Inmates order from their tablet, workers print out the orders from a computer, fill plastic bags with goods and sort them into wheeled carts for delivery. Orders meant for prisons in Springfield, Rapid City, Yankton or Pierre get boxed up to be shipped out.

“It’s like Amazon, right?” Maj. Hanson said.

Kind of. I’ve toured that Sioux Falls distribution center. There were a lot more robots than zero. Also, I didn’t see seven pallets of ramen noodles — far and away the most popular item in the commissary catalog — but I’m sure the folks at Amazon have a few pallets stashed somewhere.

Tour takeaways

Media tours of state facilities should be normal, not news.

That it’s been so hard to get inside the pen as the state debates the most expensive taxpayer-funded project in state history — which is what a new prison will be if it ever gets built — is and has been disturbing.

It’s a fact made more disturbing as we continue to hear about fights, unrest, drug deals, gang fights, assaults on officers and overdose deaths.

That’s what I was thinking during the sales job.

I wasn’t blown away by what a dump the place is. It was a lot louder and messier than I remember, but the cells are still tiny and it’s still hot as blazes.

There are countless ways a new building, properly managed and maintained, would be safer and saner for all involved. Even those who call the place functional and reckon we can’t afford a new one wouldn’t argue otherwise.

That was also true 40 years ago. We’ve made do for a long time.

What’s true today is that the debate of this moment, while the state is flush with squirreled-away prison construction cash thanks in part to federal COVID relief awards, had been a closed off, take-it-or-leave-it affair until this year.

Before Gov. Larry Rhoden appointed the task force and set it to work in a series of public meetings, there were no public forums. The Lincoln County farm ground set to host the initially planned $825 million prison? That site was selected, not debated. Lawmakers got to visit the prison if they complained loudly enough, but reporters were forbidden.

The person to blame for all that might be on Fox News right now, talking about Texas floods or immigration raids.

“The old administration went to another job,” Wasko said when I asked her about the sudden shift in transparency, a reference to former governor and now Department of Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem. “We have a new administration that has different philosophies and different outlooks on our ability to talk about things.”

Under Rhoden thus far, she said, “I have been allowed to be responsive.”

Noem didn’t so much discourage transparency, Wasko said. It was more that when a question came in, there would be “a conversation that was had,” during which the department might be told “you know what, right now is probably not the best time” to answer.

Which sounds a lot like discouragement to me.

Let’s hope we’ve left that behind us.

Get the latest news on prison construction: Sign up for our free newsletter