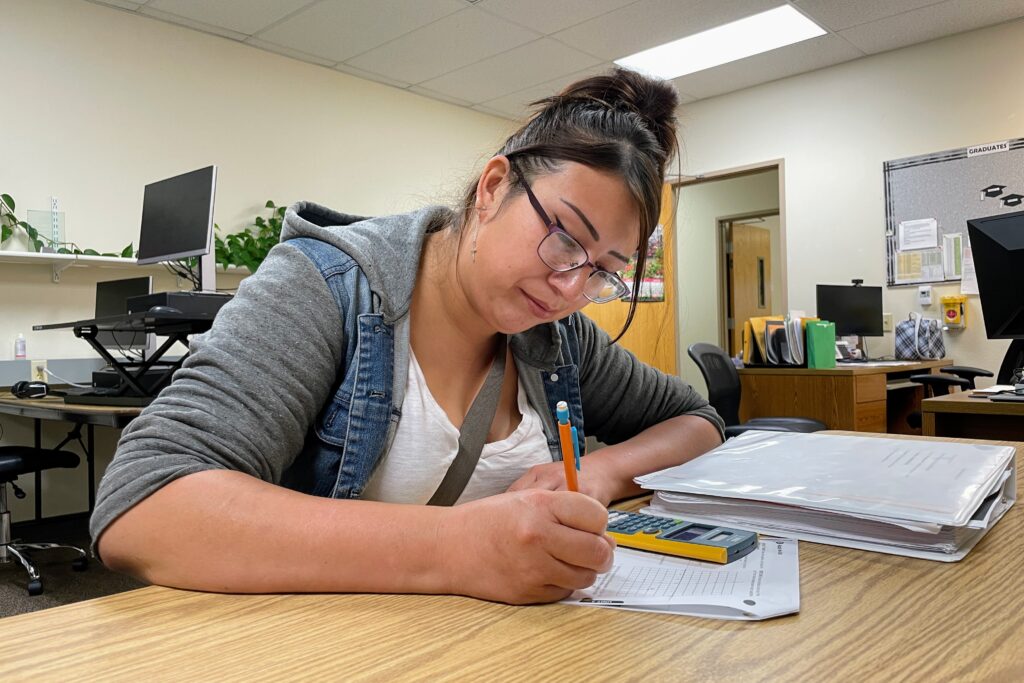

Autumn Tree Top works on a math problem on July 17, 2025, at the Career Learning Center of the Black Hills in Rapid City. (Seth Tupper/South Dakota Searchlight)

Autumn Tree Top knows what a high school certificate means.

It can mean higher pay, college and a career.

It can mean setting an example for her children.

It can mean stability, fulfillment and confidence.

Each morning, the 29-year-old mother of three wakes up early and goes to school at the Career Learning Center of the Black Hills. She works at Taco John’s as a shift manager and lives at OneHeart transitional housing in Rapid City.

Tree Top, who is Lakota, wants to become a social worker, or perhaps work with kids. She believes her personal experience with addiction, dropping out of school, homelessness and interacting with the justice system will help her connect with those she serves. Staff at the center are helping her decide what path is best.

South Dakota schools left ‘scrambling’ after feds withhold $25.8 million in funding

She started working toward her high school equivalency certificate this year and just has to pass her math test before her children can watch her walk across the stage.

“It’s challenging. But it’s helping me feel like I’m achieving something I missed an opportunity for a long time ago,” Tree Top said. “Now I get that chance again.”

That chance is in jeopardy for thousands of South Dakotans like Tree Top, according to directors of adult education centers.

The U.S. Department of Education paused distribution of $6.8 billion in congressionally approved funds for schools and educational programs on June 30, saying it was reviewing the funding to ensure it’s spent “in accordance with the President’s priorities and the Department’s statutory responsibilities.” The department has since released $1.3 billion for summer programs and before- and after-school programs, but the rest remains out of reach for schools and adult education centers.

Advocates warn of economic ‘ripple effect’

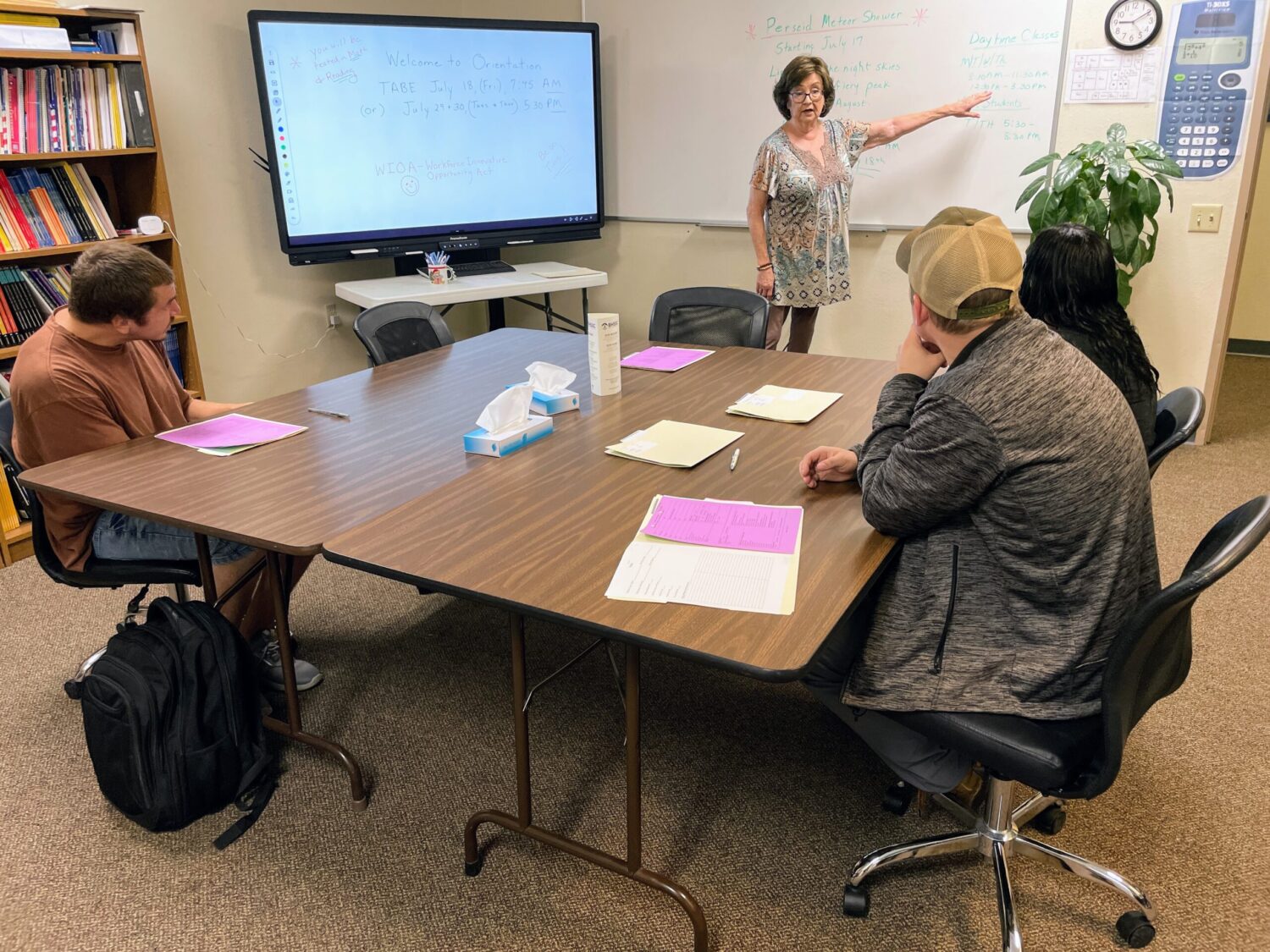

Adult education programs help students prepare for high school equivalency exams, such as the GED tests. That credential allows South Dakotans to apply for college, enroll in an apprenticeship program or apply for a job that requires a diploma. The programs can also offer civics and citizenship instruction; workplace, health, family and digital literacy training; and correctional education for prisoners reentering society.

Adult education advocates worry not only about the paused funding, but about potential future funding cuts, said Sharon Bonney, CEO of the Coalition on Adult Basic Education. President Donald Trump has attempted to dismantle the federal Department of Education, and his budget request in May included $12 billion in spending cuts for the department. Some advocacy groups have said the budget proposal doesn’t include funding for adult education.

Given the “number of victories” Trump has secured this year, Bonney expects “he’ll have his way” on education spending, too.

Bonney said programs nationwide anticipate layoffs and closures. That would create a ripple effect in the workforce and economy, she said, keeping people from getting the education they need to find a job, go to college or increase their pay.

South Dakota reported 1,833 adult learners in the state based on the latest available data. Just under 15,000 working-age adults in South Dakota aren’t in the workforce and don’t have a GED certificate, while another 39,129 are working without high school credentials, according to the National Reporting System for Adult Education.

Loss in federal funding ‘destroys’ SD programs

Federal funding on average accounts for 45% of adult education government funding in South Dakota, based on 2024 grant awards.

South Dakota programs haven’t received $1.4 million in funding due to the freeze. In 2024, four adult education organizations and two school districts received a combined total of $1.26 million in federal funds to operate. The state covered another $1.2 million.

The state Department of Labor and Regulation is sending adult education organizations some funding leftover from last year’s grants and state general fund appropriations. The money will help fill gaps through the end of September, according to a department spokesperson.

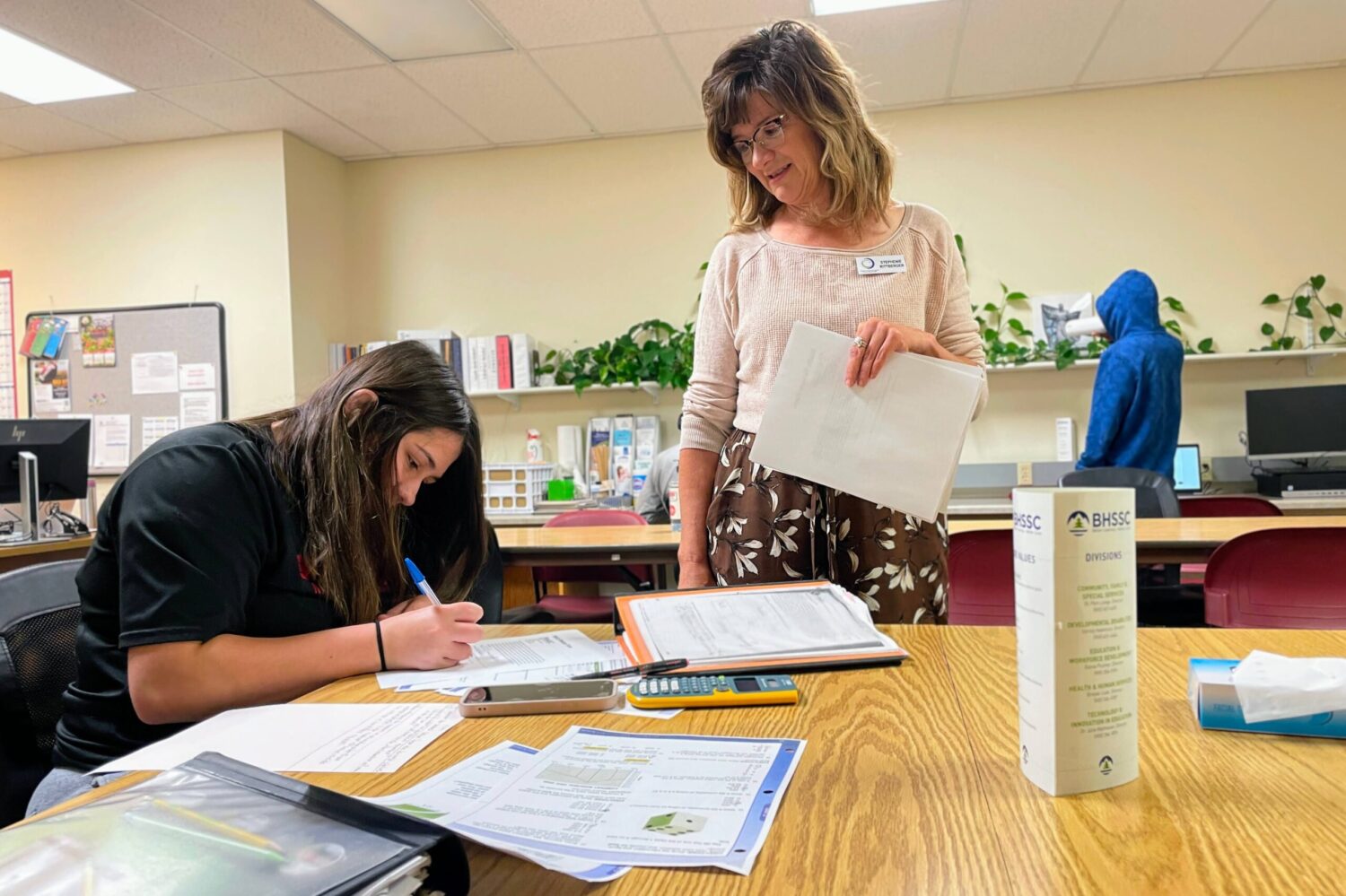

Black Hills Special Services operates the Career Learning Center that Tree Top attends. It received $513,710 in combined state and federal funding in 2024 — 100% of its operating budget, according to Stephenie Rittberger, adult education coordinator. Federal funding accounts for 32% of its budget.

Of its 517 students, 428 self-report as low-income, a majority are Native American, 101 live in unstable housing and 68 experienced homelessness in the last year.

Demand for adult education is growing in the Black Hills and Rapid City area, Rittberger said. Less federal funding could mean cutting programs and forcing students to sit on waiting lists.

A 32% gap in funding due to the federal loss is something Rittberger said local businesses and local governments can’t fill, especially when they’re already contributing. While state and local funding make up the center’s entire operating budget, other entities donate space for classes. One local nonprofit provides funding for test scholarships, which students would have to pay for otherwise.

Federal changes to food assistance will cost South Dakota $5 million annually

“I can’t expand, I can’t look at what’s better or what’s next,” Rittberger said. “I need to look at how to keep my sites as best I can because I know when rural places or Rapid City loses a service, it takes years to get it back.”

For Cornerstones Career Learning Center, a Huron-based adult learning program with offices across eastern South Dakota, a nearly 50% shortfall in its operating budget “destroys” its program. It will have to cut the number of people served or shrink the geographical area, said Executive Director Kim Olson.

The organization receives more from the state and federal government than any other adult education center in South Dakota: $783,310 in 2024, including $392,810 from the federal government. It provides virtual adult education classes to 836 people across the eastern half of the state.

Rittberger and Olson said adult learning centers plan to ask for more state funding to replace the potential loss in federal funding. Meanwhile, legislators learned this week that they’re facing a tight budget next year with revenue potentially $25 million short of projections.

Adult education delivers a return on investment, advocates say

Students and staff both feel the stress of the funding freeze, Rittberger said. Teachers feel devalued, and students are worried they’ll lose a safe place to learn.

Cynthia Roan Eagle, 54, has been working toward her GED certificate since 2002. Roan Eagle, who is a member of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe, said she is disabled, stemming from an abusive childhood that kept her from graduating high school.

“It’s been trying. I’ve been off and on because of jobs or because I lost the motivation,” Roan Eagle said. “But now I have it. I’m doing this for myself. No one is going to get my diploma for me.”

Roan Eagle works on a mobile cleaning crew at Ellsworth Air Force Base, a job she secured through disability services organization Black Hills Works. Her pay increased from $11.25 to $17.25 an hour because of her increased critical thinking skills and passing subtests on her way to get her GED certificate.

After more than two decades watching her friends and peers earn their credentials, she’s ready. She plans to pass her last test in January and perhaps start taking college courses through Oglala Lakota College or at Black Hills State University. She said Rittberger offered to sit in on some classes with her to see if it’s the right fit.

“If this program is pulled, there’s no way to do this. You can’t get a good paying job, you can’t go on to higher education, you can’t do anything,” Roan Eagle said. “We need this program because it helps a lot of people, including myself.”

English classes, literacy ‘help America become great’

At Cornerstones, 69% of students are English language learners, while the remainder are working on their GED exams.

Federal fallout

As federal funding and systems dwindle, states are left to decide how and whether to make up the difference.

Rosemary Hicks earned her GED diploma at 58 years old in March. Originally from Brazil, Hicks and her teenage daughter were deserted by their abusive husband and father in the United States while visiting on a tourist visa in 2017, she said. While she stayed in a women’s shelter in Huron, she was encouraged to take English classes and apply for a green card to become a U.S. citizen.

Hicks is on track to earn her citizenship in September. After that, she plans to take college courses to start a new career in psychology. She currently cleans rooms at the Huron Regional Medical Center — a job she was only able to secure after passing her GED tests.

Earning a better education earns a better future for herself and her daughter, she said, but also for her new country. Without Cornerstones, Hicks said, she wouldn’t have been able to advance in her life or work.

“I feel safe here. I feel comfortable here. I feel grateful, and I will say to everybody: Stay in school until you can do that,” she said. “No matter if you’re a young adult at 25 or a grandma like me at 58, the important thing is to continue and learn and help America become great.”

Stay current on the state impact of federal actions: Sign up for our free newsletter.