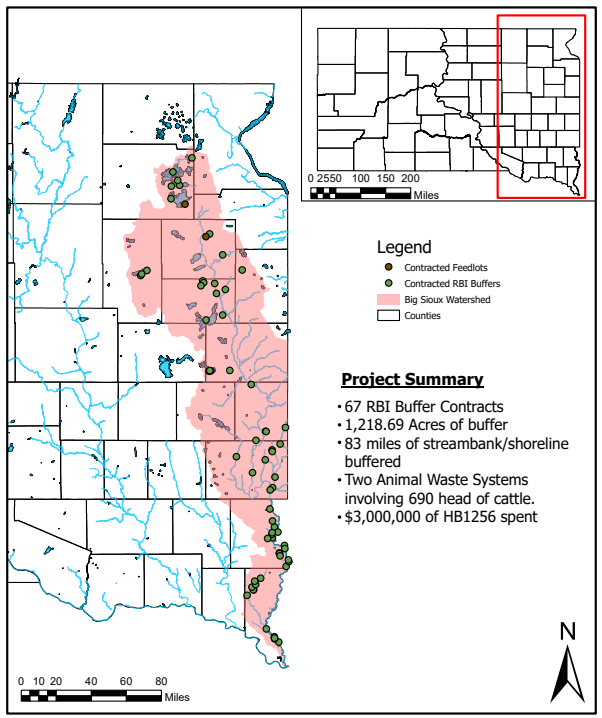

A section of Blue Dog Lake shoreline before and after the implementation of a South Dakota state government program paying for buffer strips to improve water quality. The program covered the Big Sioux River watershed. (Photos courtesy of the Department of Agriculture and Natural Resources)

As a public debate begins about agriculture and water pollution in South Dakota, a new report shows the effects of a $3 million effort to mitigate the problem.

South Dakota’s top state Senate Republican and the governor sparred this week over whether the state should tighten agricultural regulations to address water pollution. Senate President Pro Tempore Chris Karr, R-Sioux Falls, told a legislative committee that with most monitored rivers and streams in the state too polluted to support at least some uses, such as swimming, fishing or boating, the state can no longer “dance around” the idea of more regulations on agriculture.

Gov. Larry Rhoden, a rancher, blasted those comments as “misinformation” made “out of ignorance” and said Karr would be “set straight.”

With so much polluted water, SD lawmaker says state can no longer ‘dance around’ ag regulations

Meanwhile, a final report quietly emerged about an effort to keep cattle waste out of lakes and streams and reduce chemical and sediment runoff from farms. Karr was the prime sponsor of the bill that created the 2021 initiative. The state Department of Agriculture and Natural Resources managed it. It paid $3 million to help landowners contain livestock waste or plant grass and other vegetation along streambanks in the Big Sioux River watershed.

Jay Gilbertson, manager of the East Dakota Water Development District, said the enrolled vegetated strips, called buffers, filter pollution and stabilize stream banks. Livestock are required to be kept out of the areas for part of the year, except during limited times and circumstances when grazing and haying are allowed.

According to the report, 67 projects created 83 linear miles of buffers, protecting 1,219 acres. The project contracts last for 10 years. They prevent an estimated 1,484 pounds of phosphorus, 6,415 pounds of nitrogen and 953 tons of sediment from entering the Big Sioux River watershed each year.

Payments increased after low interest

The program started slowly. Nobody had signed up for it by January 2023, two years after it was approved.

“The feedback that we got back was that we’re not paying enough to really move the needle,” Hunter Roberts, secretary of the Department of Agriculture and Natural Resources, told lawmakers at the time.

So, the department began paying more.

Governor says lawmaker will be ‘set straight’ on suggestion to regulate agricultural water polluters

DANR materials say that under the original cash-incentive program, a 50-foot, half-mile buffer under a minimum 10-year contract would have yielded a total payment of about $5,000 for cropland and $1,300 for pastureland over 10 years. Under a new formula Roberts outlined, the rates for the same examples increased to about $13,000 for cropland and $3,400 for pastureland.

Additionally, the department allowed the funds to be spent on livestock waste containment systems. Two of those were installed, involving 69 cattle. The department also allowed landowners to “stack” their program payments on top of payments from the federal government’s Conservation Reserve Program, which pays landowners to take marginal land out of agricultural production. That meant landowners could receive both federal and state payments for eligible acres, plus another incentive if those stacked acres are enrolled in a Game, Fish and Parks program that pays landowners to allow public access for hunters.

“Everybody seems to like free money or at least additional money,” Gilbertson said. “And these activities got the ball rolling, and it turned out to be pretty popular.”

Gilbertson credited lawmakers, including Karr, for launching the initiative.

“It was a great example of the Legislature stepping forward, stepping up and saying we need to invest in our natural resources here in South Dakota,” he said.

Benefits and worries beyond 10 years

Sushant Mehan is an assistant professor and water resource engineer at South Dakota State University. He and a team are quantifying how the buffer initiative changes vegetation and downstream water quality.

He said buffers are often on flood-prone, low-yield acres, and the research already shows enrolled acres are more productive during the times when grazing and haying are allowed than they would be under year-round grazing.

“So, if people go that route, ultimately, it’s a win-win situation for them,” Mehan said.

Mehan frames the benefits of buffers as both direct for landowners and indirect for everyone paying a water bill. He said filtering out contaminants is a costly business for water systems, and those costs are passed along to customers.

Mehan said the next step is figuring out where buffers will do the most good. The team’s ongoing work is about mapping which enrolled acres are “truly critical” to maximize water-quality gains.

Gilbertson worries that maintaining the buffers after the 10-year contracts expire could be difficult if landowners expect a similar payment.

Paul Lorenzen administers the state’s watershed protection program for the Department of Agriculture and Natural Resources. He said the program included cost-sharing for fencing and alternative water sources. He said once those investments are in place, landowners may choose to keep the buffers even after the checks stop.

Lorenzen said other programs with similar 10-year commitments have seen producers stick with the practices once they experience the benefits, and he hopes buffers will follow the same pattern.

A report from the state Department of Agriculture and Natural Resources on a Big Sioux River watershed riparian buffer program.