Study links space data to ag, ranching, and drought planning in South Dakota

BROOKINGS, S.D. – South Dakota State University researchers have shown that satellites can now track how plants grow, live, and die in some of the toughest landscapes on Earth.

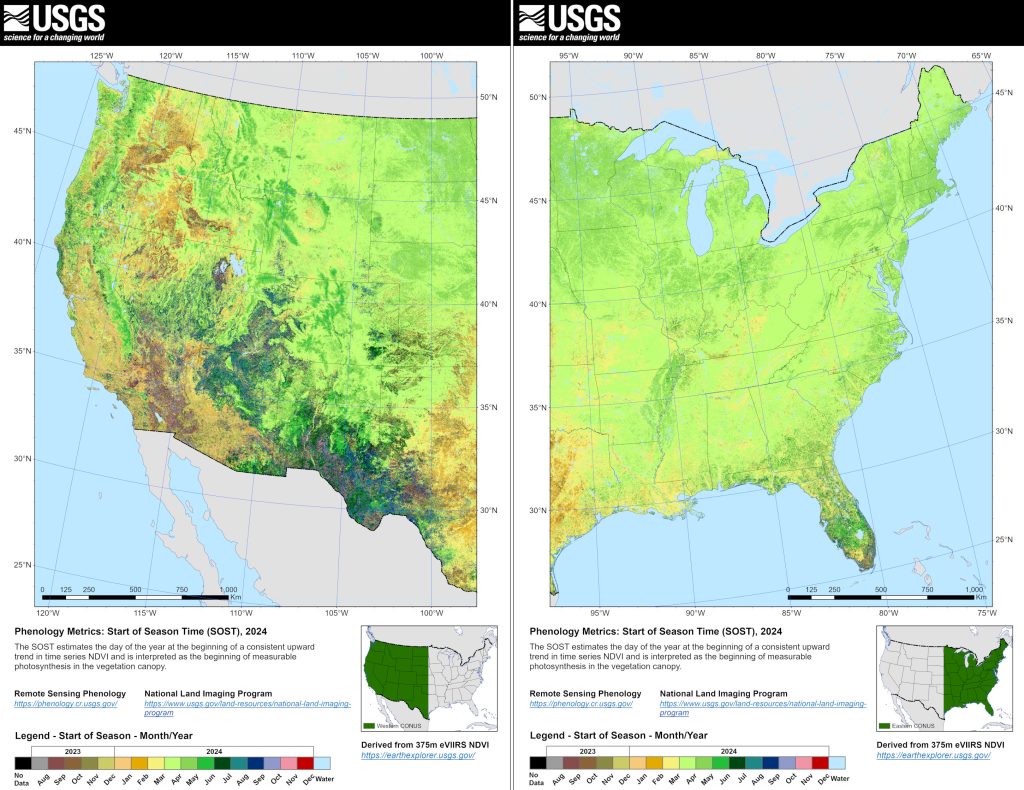

A study by SDSU’s Geospatial Sciences Center of Excellence, published in the ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing, tested PlanetScope satellites—small “Dove” satellites launched by Planet Labs of California—over semi-arid areas of the western United States.

Why It Matters

The findings matter close to home. Semi-arid conditions affect much of the Northern Plains, including South Dakota. By tracking how grasses, shrubs, and trees respond to rain and drought, SDSU’s work could help farmers fine-tune planting and harvest schedules and give ranchers better tools for managing forage for cattle. State leaders also point to the value of this research in preparing for drought cycles that increasingly strain water and land resources.

Semi-arid regions cover about 15 percent of Earth’s land and support roughly two billion people through crops and livestock. These dry areas are highly sensitive to drought and climate change, making it vital to know when plants start growing, reach maturity, and go dormant.

Until now, satellites have often struggled to pick up these seasonal changes. Vegetation in semi-arid zones grows in short, irregular bursts after rain. Traditional satellite data missed much of this.

The SDSU team, led by Distinguished Professor Xiaoyang Zhang and postdoctoral researcher Yuxia Liu, compared PlanetScope satellite images with ground-based PhenoCam cameras at 15 sites across the West. The PhenoCams, equipped with infrared sensors, captured close-up views of grasses, shrubs, and trees.

The researchers found that PlanetScope satellites were especially accurate at detecting the start of plant growth in spring. The satellites sometimes lagged by a week or two when tracking plants as they dried and went dormant in the fall.

Even with those delays, the satellites proved capable of capturing plant growth cycles at a fine three-meter resolution—detailed enough to separate grasses from shrubs and trees.

“This ability will inform planting and harvest times, drought response strategies, and livestock forage planning,” Zhang said.

Liu added that the findings show “promising potential” for using satellites to monitor plant growth in dry climates worldwide.

The research highlights SDSU’s growing role in space-based earth science and its importance for agriculture, ranching, and climate research in the Great Plains and beyond