BLACK HILLS, SD — “When we heard the warning we thought he was kidding. We just sat there, and pretty soon this big bunch of water came down the creek. We ran next door and suddenly the water was up to my neck”. What would be an aptly chilling quote to see among the myriad of painful stories of the flooding along the Guadalupe river only a few weeks ago comes from the mouth of Davis Heraty, a teenager at the time of the 1972 Black Hills Flood that led to the deaths of over 238 people.

At times of great tragedy, those in the Black Hills often wander to that grave cultural memory, whose survivors still live with us today. We feel a great deal of painful empathy in knowing that the hardship and cold cruelty of nature has been delivered onto someone else, and we seek to find common ground and common experience with the survivors, that such tragedies might be more easily recovered from and prevented from happening again.

With this in mind, we at the Rapid City Post have been researching both events tirelessly over the past several weeks, to the greatest extent we are able to understand the facts of both tragedies, so that we might join hands with our fellows in Texas. We will showcase the similarities and differences underlying each event, and how our past might help Texas’ future.

Both events are tragedies with a severe and devastating human cost, and we wish to make clear that both events are not meant to be lessened by comparison to one another, nor victims disrespected, rather it is simply us seeking to understand the pain of those today and contribute to efforts making sure this sort of event will not happen again in the future.

The Texas Flood

The threat of flooding in Texas was understood at least two days in advance of the disaster itself. State resources were activated in anticipation of the event and the day when the National Weather Service (NWS) gave short-term guidance warning of flash flooding local leaders gathered to discuss potential flooding. During this, said local leaders were given independent responsibility to respond in the event of a natural disaster. At 1:18pm the short-term guidance is upgraded to a flash flood watch, and reports go out warning about potential flash flooding in central Texas over the course of the next several days.

At midnight, a staffer at Camp Mystic in Texas reported watching the rain gauges, and that many were offline. At 1:14am the NWS issued a flash flood warning, which was received by staffers at the camp, however they did not begin evacuations until nearly an hour later. Around 3:30am a firefighter calls dispatch to report the Guadalupe river is rising, and only minutes later Kerrville City Manager Dalton Rice reports first responders are being swept away by flood waters.

Around 5:00am the Guadalupe River reaches its height at nearly 23.4 Feet, and rain gauges go offline for a period of three hours. The Guadalupe River does not recede until 3pm, however a half hour later, after nearly two hours of reported flooding the first recorded wireless warnings are issued to the general populace.

A unit identified only as unit 51 requests command be advised of the situation. Dispatch responds, stating “Sir, we don’t have an incident command right now”.

Near 6:00 am the Coast Guard are informed, but are waylaid for eight hours due to the intensity of the flooding. By noon on July 4th, the event is declared a disaster by officials.

The Black Hills Flood

The Black Hills Flood (also known as the Rapid City Flood) began with a much shorter window of warning than its more recent counterpart. The National Severe Local Storm Forecast Center (Now Known as the Storm Prediction Center) advised the black hills of potential strong storms at 9am on June 9th, though this seems to have not been detected by local weather forecasting until Ellsworth’s weather radar detected the incoming system.

By 5pm, rains began, and reports of flooding by 6pm from county sheriff’s departments led to state radio dispatch requesting radio and tv stations warn motorists to avoid certain roadways. According to a story recorded by Corey Christianson, author of The 1972 Black Hills Flood, “Mayor Barnett actually was down at Canyon Lake, watched the water rise and rise and rise and rise, went and tried to open the pipes himself to get them even further open, and then he started going door to door and trying to get people out of their homes”.

By 6:30pm Rapid Creek was rising rapidly, and the National Weather Service warned of flash flooding nearly an hour later, around the time the mayor activated the national guard, police, sheriffs department, and highway patrol to aid civilians. At 7:45 a Nemo resident reports flooding upstream of Box Elder Creek and the NWS warning is expanded accordingly.

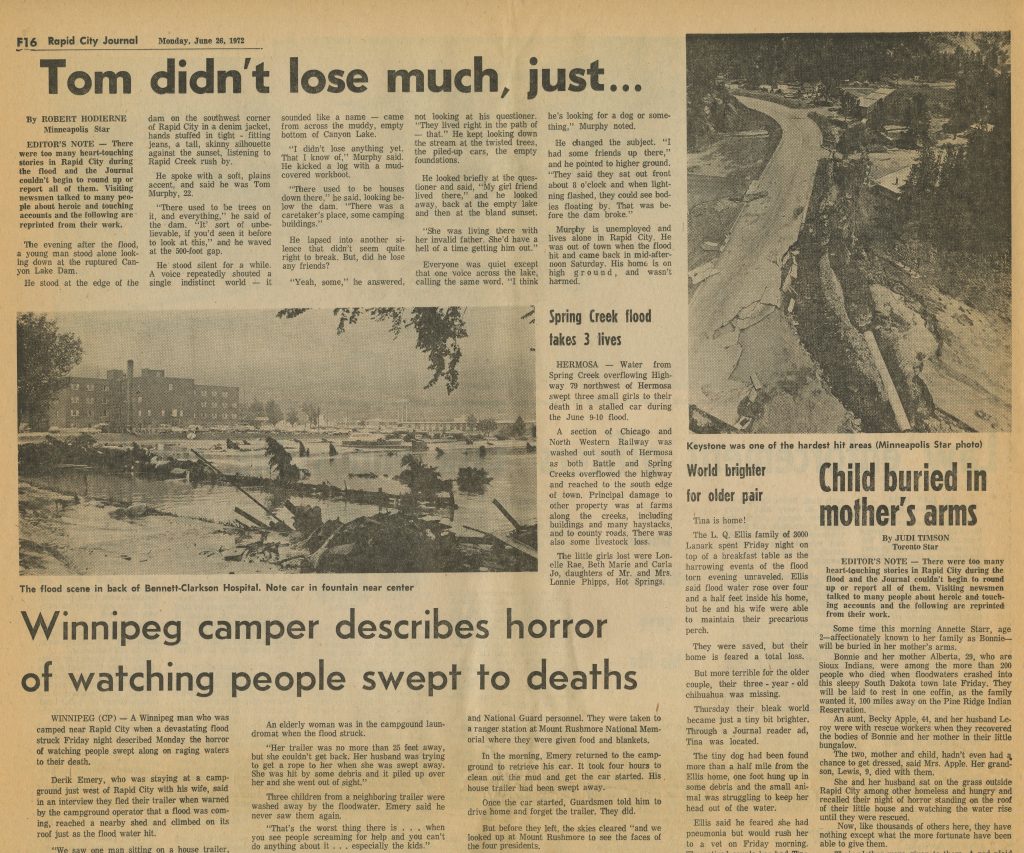

Around this time Keystone, which is built along Rapid Creek flooded, leading to eight fatalities. Sturgis flooded as well, which thankfully had no fatalities but caused massive property damage for local families.

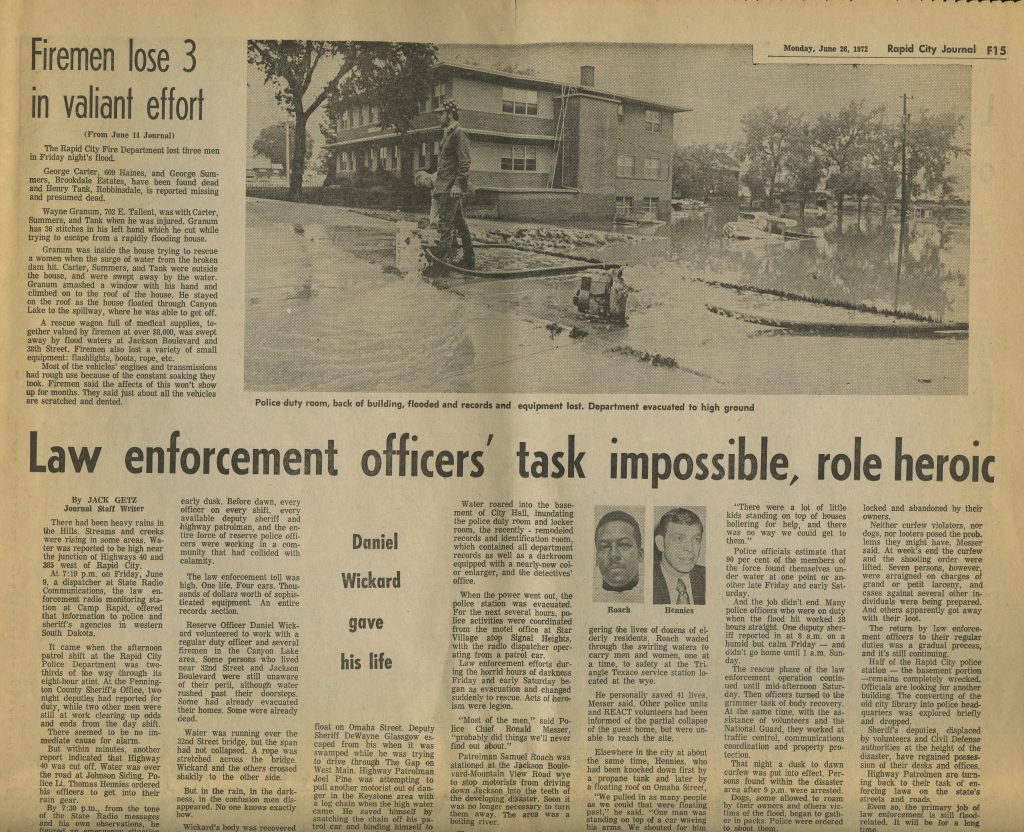

During this, existing alarm systems were quickly made non-operational amid rising waters, which fragmented emergency communications. During this time as well, the NWS’s Rapid City Airport office became largely unresponsive as telecommunications was destroyed.

At 10:45 pm, Canyon Lake Dam fails, and a flood crest with an estimated flow rate of 50,000 Cubic Feet Per Second (over one billion gallons per hour) reached downtown by midnight. Rapid Creek reaches a maximum depth of nearly 16 feet, before receding by 5am.

Similarities And Differences

While these floods are both separate in distance, they are deeply connected in the similarities of their events when the flood begins. At once we can see from this the immense progress which we have made, and how far we still need to go in regards to preparedness, response, and in the infrastructural decisions which made this degree of flooding possible.

To get ahead of potential thoughts a reader might have following both accounts: It is not my intention to say that we should point fingers at any individual on the ground floor of this disaster in either event. A natural response to fear is to freeze or become otherwise indecisive, and nothing is gained nor justice served for those who died in either case by blaming people for acting human. These sorts of tragedies– these grand displays of nature’s fury are often wholly beyond the ability of training and discipline to manage, and so we must look at how we may have better prepared for those chilling moments of rapidly-escalating disaster.

However, as Christianson said in an interview with The Rapid City Post, “When you put all these things together, you’re talking about a failure of the emergency alarm system. You’re talking about the failure of dams all the way from North Black Hills all the way down”. As she says after, technology was a lot less advanced than the technology we see today, however we see a lot of this in both the Black Hills Flood and the Texas Flood.

While an obvious technological leap has occurred in the intervening decades the primary issue which likely caused hesitation on the ground where there may have otherwise been none is that there was, in both cases, little public communication on the part of governing bodies confirming flooding– In the case of Rapid City, alarms that would have normally warned citizens of the impending flood were destroyed quickly. When the NWS issued a flash flood warning in texas, this should have come with responsive wireless warnings, as while many were likely not asleep, or not tuned in via TV or Radio to hear this announcement, many sleep with their heads next to a phone, and a warning to area phones would have most likely been more widely received.

The second largest failing which could have likely saved lives is in planning. In both cases, planning with the environment and changes therein had not been considered when it comes to allowing building along the flood plain of both waterfronts. As flooding becomes more severe in the US year-by-year and emphasis is being made to cut regulation and spending, we need to remember that for as much of that regulation is based on things that could be seen as “possibilities” rather than “certainties”, some of those possibilities exist for a reason, and with reasonable forethought or past experience backing them.

In planning as well, we can see an abject failure on both sides when it comes to organization both beforehand and during. Reporting from Texas around the time seems to support that the response was disjointed, It is natural to want to believe that flooding cannot happen in a location if it does not happen frequently or regularly– we can see this in both cases, however in the case of Texas, authorities had forewarning days ahead of time, but were given the individualized authority to decide whether to take action. With this incident happening in the morning many were asleep at the time of the flooding, and others, perhaps waiting for confirmation from nearby areas for a flood they may not have been certain was happening became victims of the Bystander Effect. For this, there should have been an emergency response team set up to provide more directed command of response and communication.

The core difference of this is potentially the effect climate change may have played in Texas flooding. On average, global temperatures have risen around one degree celsius from 1900 to 2000, and whether you believe this is human-caused or not is irrelevant in this situation, as with or without that belief most who have lived on this earth for more than a few days can agree that ice melts under heat, becomes water, and that water globally becomes rain. This was seemingly not accounted for in Texas’s 100-Year floodplain, and thus homes were built in danger zones they may not have otherwise been.

Another is timing, while flooding occurred in the evening and overnight in the Black Hills, likely hindering citizens’ ability to respond, Texas’ occurred primarily in the late night and throughout the next day, when more people would have been sleeping. While this is not beyond the ability of modern technology to account for (as stated prior, most people sleep near their phones), it is something that must be accounted for when comparing these two events.

Recovery

While Texas’s recovery efforts are ongoing, we may learn a little bit at least from the response. In response to this flood, the at-the-time sedentary Rapid City put forth initiatives to stop homes from being built on the flood plain of Rapid Creek (much to the chagrin of incoming developers, even today). In addition to getting more accurate, updated flood plain mapping for the Guadalupe, this is a necessary step in preventing more loss of human life in the future.

Additionally, more robust warning systems were put in place following the Black Hills Flood. “There new emergency monitors have been installed in all these creeks. So there’s new monitoring stations all along Rapid Creek and some other creeks in the Black Hills, just to prevent this from happening again,” said Christianson.

During the Black Hills Flood, FEMA did not yet exist, and so humanitarian efforts were highly individualized and disjointed. While bases like Ellsworth opened to those displaced, while friends and neighbors allowed the flood’s myriad of victims into their homes, and while the Department of Housing set up trailers, no body existed dedicated to emergency response. In Texas, delays and setbacks caused by the Trump Administration’s dismantling of the organization as part of austerity measures has made the department’s response sluggish, understaffed, and also marred in bureaucracy put in place by Secretary Kristi Noem.

In practical terms, it was as if the organization designed for a rapid response to these sorts of disasters was not there.

Conclusion

The conclusion to this is certain. For the good of people and of human life, we need to be better. We should not be pointing fingers at individuals, but rather questioning why individuals who were part of a complex system were not able to perform adequately to prevent the loss of human life, and what practical and material measures may be taken to prevent this loss in the future.

As recovery continues, we will be here with those displaced by the flooding. We need to be with them after as well, because just as easily as it happened to them, these situations can happen to us, but it is our ability as those witnessing history and history in the making to prevent them.