An economic assistance application for the South Dakota Department of Social Services. (Photo illustration by Makenzie Huber/South Dakota Searchlight)

Changes to Medicaid could leave thousands of South Dakotans uninsured and impair an already fragile rural health care system, advocates worry. But a concurrent $50 billion in federal funding for rural providers nationwide over the next five years could blunt the impact on the system.

That’s a “mixed bag for South Dakota,” said Shelly Ten Napel, CEO of the Community HealthCare Association of the Dakotas.

President Donald Trump signed changes into law earlier this month as part of his One Big Beautiful Bill Act. The changes to the state-federal health insurance program for people with low incomes aim to rid the system of fraud and waste and save the federal government $1 trillion over a decade, according to Republicans who supported the bill. The savings support tax cuts prioritized by Trump, along with new spending on immigration control and defense projects.

The nonpartisan health research organization KFF estimated 13,000 South Dakotans could lose Medicaid coverage, primarily by failing to meet new work requirements. Combined with the expected expiration of the Obama-era Affordable Care Act’s enhanced premium tax credits at the end of this year, the projected number of uninsured South Dakotans rises to about 20,000, according to KFF.

Key changes to Medicaid aside from work requirements don’t significantly affect South Dakota, state Department of Social Services officials said. The state doesn’t rely on provider taxes capped in the law, doesn’t have problems with deceased or duplicate people enrolled, they said, and uses a different type of payment model than other states. Medicaid Director Heather Petermann said South Dakotans should not “despair.”

“South Dakota is in a much different place,” Petermann said. “When people hear the news of ‘doomsday is coming,’ but it reflects the kinds of cuts that are occurring for states that use other types of models or mechanisms to pay for Medicaid than South Dakota does, that projects fear instead of informing people that there’s going to be a pathway for them.”

How work requirements will affect state government, hospitals

South Dakota had proposed its own Medicaid work requirements, but Department of Social Services Secretary Matt Althoff said the state will withdraw those now that work requirements are included in the new federal law.

By 2027, states must require able-bodied Medicaid enrollees to work or volunteer 80 hours a month or be in school at least half-time. Exemptions include people who are pregnant or postpartum, disabled, eligible for the Indian Health Service, and recently released from incarceration, among others.

South Dakotans voted in 2022 to expand Medicaid to adults with incomes up to 138% of the poverty level. Most South Dakotans on expanded Medicaid already work or would meet the exemptions, according to Ten Napel.

“It’s unfortunate there has to be a lot of administrative work just to confirm that,” she said.

The federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services must release additional guidance by the end of this year, leaving a year before the work requirement implementation guideline. Althoff said he’s confident South Dakota can meet the deadline.

He’s unsure how the new requirements will affect the state’s budget, since it’ll mean an upgrade in technology and potentially more staff. The change requires Medicaid recipients to verify their eligibility more frequently.

“That is precisely why we want to lean in to technology,” Althoff said. “Can we do twice the workload of determinations with the equivalent amount of staff?”

Althoff told lawmakers on the state’s budgeting committee this month that he is unsure “all of the federal dollars for one-time costs will meet” the state’s needs for Medicaid changes.

State officials aren’t sure how many South Dakotans will remain on Medicaid, especially because the change requires applicants to meet work requirements for four weeks prior to enrollment. As of June, 29,843 South Dakotans were enrolled in the expanded portion of the Medicaid population. There were 144,310 total Medicaid recipients in the state.

Ten Napel urged caution, suggesting the state should apply for an extension to ensure the program is set up properly before it’s implemented.

“Where work requirements have been implemented in other states, we’ve seen a lot of checking in and people having to remember to do it and get paperwork done,” Ten Napel said, “and many people just drop out of coverage either because they don’t understand the requirements or because of the complexity of other things happening in their lives.”

Tim Rave, CEO of the South Dakota Association of Healthcare Organizations, said work requirements could also take a toll on providers.

“It could take two to three years before work requirements are fully implemented,” Rave said. “From there, if it impacts us as the models say it could, I think services will be cut, or potentially locations will close. We have to see how this all rolls out and what actual impacts are.”

Funding injection in rural health could soften cuts

In a statement, representatives with Sioux Falls-based Sanford Health said the law “introduces financial pressures” for health systems.

Twenty percent of hospitals in South Dakota run in the negative margin, according to Rave.

“Obviously, every facility will do what they can to remain open,” Rave said. “It’ll just be a matter of what services they’ll be able to provide.”

Services most at risk in rural areas include maternal and women’s health, behavioral health and dental, Ten Napel said.

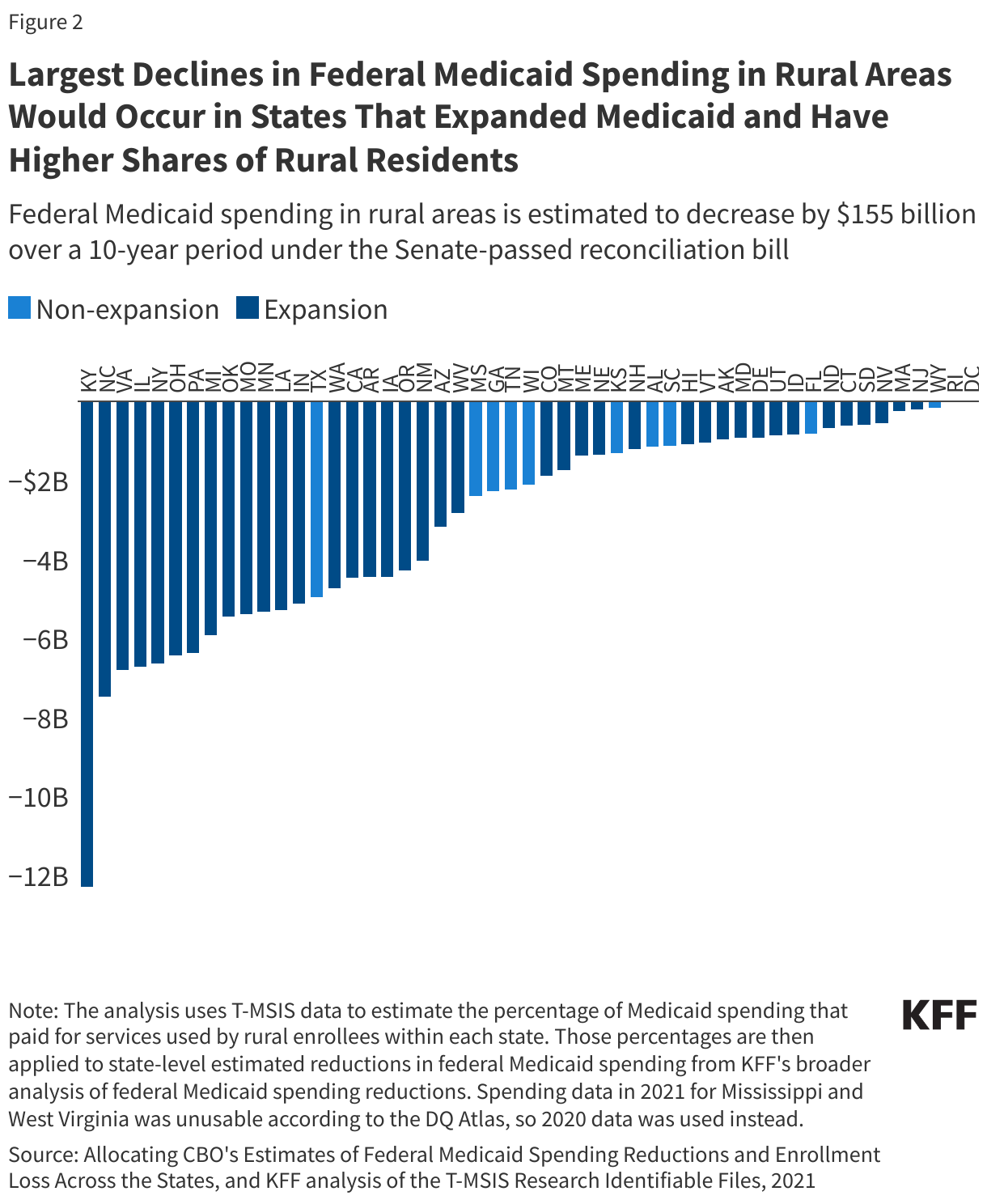

People who live in rural areas nationwide are more likely to have health insurance through Medicaid, which puts rural health facilities at risk of lost funding and a rise in unpaid care if patients lose coverage.

Concern about rural health led to the creation of the $50 billion rural health fund in the Big Beautiful Bill Act. South Dakota is set to receive at least $100 million a year over the next five years, as long as the state submits a “detailed rural health transformation plan.” The state could receive more, based on how the rest of the funding is distributed to states.

“Our budget is smaller than most states, so disproportionately, we’re probably impacted for the good,” Rave said. “It certainly doesn’t have the sting it does in other states.”

According to KFF, the largest declines in federal Medicaid spending will be in states with expanded Medicaid and higher shares of rural residents. While Kentucky will be impacted the most, losing a projected $12.3 billion, federal Medicaid spending in rural areas in South Dakota over the next decade will decrease by a projected $487 million. Questions remain, according to KFF, about how the funding will be distributed among states.

The state and health providers plan to collaborate about how the funds can be used. Ten Napel said the money can be invested in training, recruitment and shoring up rural preventative and primary care access.

“How do we invest these resources so that in 10 years, we’re in a better place than we are today?” Ten Napel said. “We know investment in the front end can save money on the back end.”

But that funding alone likely won’t “fully address the broader challenges rural providers will face,” Sanford representatives said.

“We look forward to working closely with our state and federal elected officials,” the statement read, “to implement these changes in ways that protect access, support innovation and strengthen care for rural America.”

As federal policy changes impact South Dakota, stay in the know: Sign up for our free newsletter.