Driverless tractors have been a goal for decades. A new John Deere add-on that allows certain newer tractors to perform tillage practices autonomously was tested in North Dakota

GLEN ULLIN, N.D. — It’s disconcerting to watch a tractor with no one inside fire up and drive away. Gooseneck Implement employees testing out a new precision agriculture feature from John Deere watched it happen for about a week in southern Morton County fields.

“We’ve added technology on to an existing 9RX John Deere tractor, and it is capable of running autonomously,” said Jim Campbell, equipment specialist lead for Gooseneck Implement. “So we are out here doing some tillage work today, and there’s nobody running the tractor. Nobody in the tractor at all. It’s running by itself.”

As he talked, the tractor was over a hill, working alone, breaking up some corn stubble in a field south of Glen Ullin in Morton County. The land was to be planted with canola.

The Precision Upgrade Kit that allows the tractor to operate autonomously for tillage practices is a Limited Production Build that is not yet commercially available but will be soon, according to a story in InForum. So far, it can be added to 9R and 9RX models, in model year 2022 and newer, and 8R and 8RX models going back to halfway through 2020. The implements used on the system need to be 2017 models or newer, he said.

Gooseneck Implement, a John Deere dealership with locations throughout North Dakota and in Lemmon, South Dakota, is testing out the technology so employees can gain some comfort level with it before it’s commercially available.

Autonomous efforts

Developing driverless machinery is not a new effort. An article in Popular Mechanics in 1940 noted efforts by Frank W. Andrew to develop a system that would enable a tractor to operate without a driver in circles, “like the grooves on a phonograph record.” But neither it nor other efforts took off, and the development of driverless farm technologies largely stalled until recent years.

Leader-follower systems — which rely on an unmanned vehicle following a manned vehicle — are in limited use, including at Minn-Dak Farmers Cooperative and in grain carts, like Raven Industries’ OMNiDRIVE . Numerous companies have been working to figure out driverless tractors for well over a decade . CNH unveiled concepts for autonomous tractors at the 2016 Farm Progress show .

Companies like Bluewhite and Monarch have developed autonomous systems for use in specialty crops on lower horsepower tractors. The original focus of North Dakota’s Grand Farm was around autonomous agriculture systems

The John Deere autonomous package right now is only approved for tillage. But Campbell said the basis for the program has built on existing, commonly used technologies like autosteer, and he thinks new technologies will continue to build on each other, expanding the capabilities of autonomous machinery.

“A lot of those technologies that Deere has come out with, that’s kind of the framework, the building blocks to autonomy. So that’s what we’re seeing today, is you’re starting to see all of those things come together in infield application,” he said.

How it works

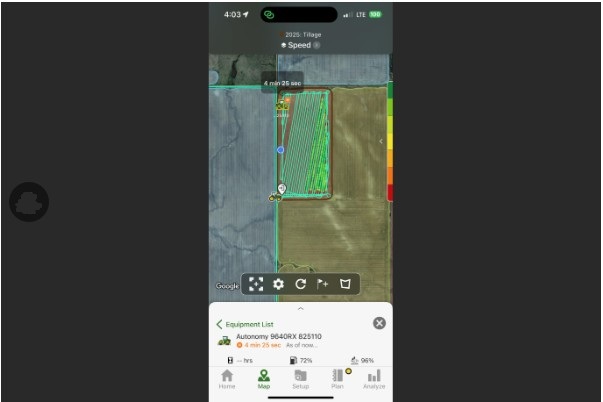

A Gooseneck employee demonstrated by moving the tractor, pulling a 49.5-feet-wide 2660 vertical tillage machine, to a new point in the field. Then he got out and walked away. When he was at least 1,500 feet away, he used an app on his phone to start the tractor. Lights flashed, horns honked, and the tractor took off across the field.

“It’s a little unnerving, if you’ve been around tractors for a long time, just to see one start heading off, and something to get used to. But I think producers will get to that. We’ll get to that state pretty quick,” Campbell said.

The system has 16 cameras to monitor what’s going on around it. The tractor won’t start if anything is within 50 feet of it.

“It’s very sensitive to objects that are obviously humans or objects that could contain humans,” Campbell said. “There’s a lot of safety that’s built into the system, and there’s a lot of double safety that’s built into the system.”

The cameras also monitor while the machine is in autonomous operation. Campbell explained images are sent to John Deere, where humans monitor anything the machine alerts on. Depending on what the cameras and sensors pick up, alerts can trigger a “common, ordinary stop,” a “partial demotion” or a “full demotion,” Campbell said.

A common stop might be from something like a deer running through a frame; if it’s determined there is nothing in the way of the machine, it starts operating again. A partial demotion could be something like a stationary object — maybe a spare tire that fell into the field — and the system informs the producer that unless he gives a different signal within five minutes, the machine will try to route around the object. After three failed attempts to get around an object, it triggers a full demotion.

Other things that could trigger a full demotion include mechanical problems like blowing a hose. In the case of a full demotion, someone has to go to the field, identify the problem and restart operations.

Campbell said too much dust obscuring the cameras can also cause a full demotion, because the system relies on the cameras to operate. When things like that become too frequent, a human can take over driving.

The tractors need to be moved from field to field and rely on someone identifying field boundaries on a map, along with obstacles to go around, like rock piles or sloughs.

“It does not recognize standing water. However, what it will do is it notices slip on the tires. So if it sees anything more than 75% slip for two seconds or more, she’s done, right? Stop,” Campbell said.

He said the system can also do some thinking for itself, just “not always the way I would have done it,” Campbell said. It might turn a different direction or do things in a different order than he would have. He compared it to his grandfather having him bale hay when he was just learning about equipment.

“You know, it’s like, ‘I did the same job as you did, Grandpa,’ but it was, ‘No, you did it, you did it wrong. You accomplished the same thing, but you did it wrong,’ ” he said.

“We kind of do the same thing. We sit around here watching. It’s like, why? Why would you go that way? You could have went this way. So now we’re, we’ve turned into grandpa talking to our grandson, going, what are you doing going that way? You’re going all the way to the end to turn around and come back all the way. Why?”

To do all of this thinking and information transmitting and sharing, Campbell said the tractor is equipped with a JDLink Boost providing satellite internet through Starlink.

“So that way, we don’t ever lose connectivity to the rest of the world,” he said.

Demand for autonomy

Campbell predicts farms struggling with labor shortages will be interested in autonomous systems like the add-on from John Deere. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics , about 116,400 openings for agricultural workers are projected for each year through 2033 to replace workers who transfer to other occupations or leave the labor force.

“This technology can allow tasks to be done while maybe other higher-priority tasks need to be completed first. You just don’t have the resources to spread everywhere,” Campbell said.

However, he also thinks it might take some time for people to trust the technology.

“You’re going to have that standoffish about, just not sure about that kind of level of technology, until they can start to see where they can really become more efficient in their operation with the resources that they have,” he said.