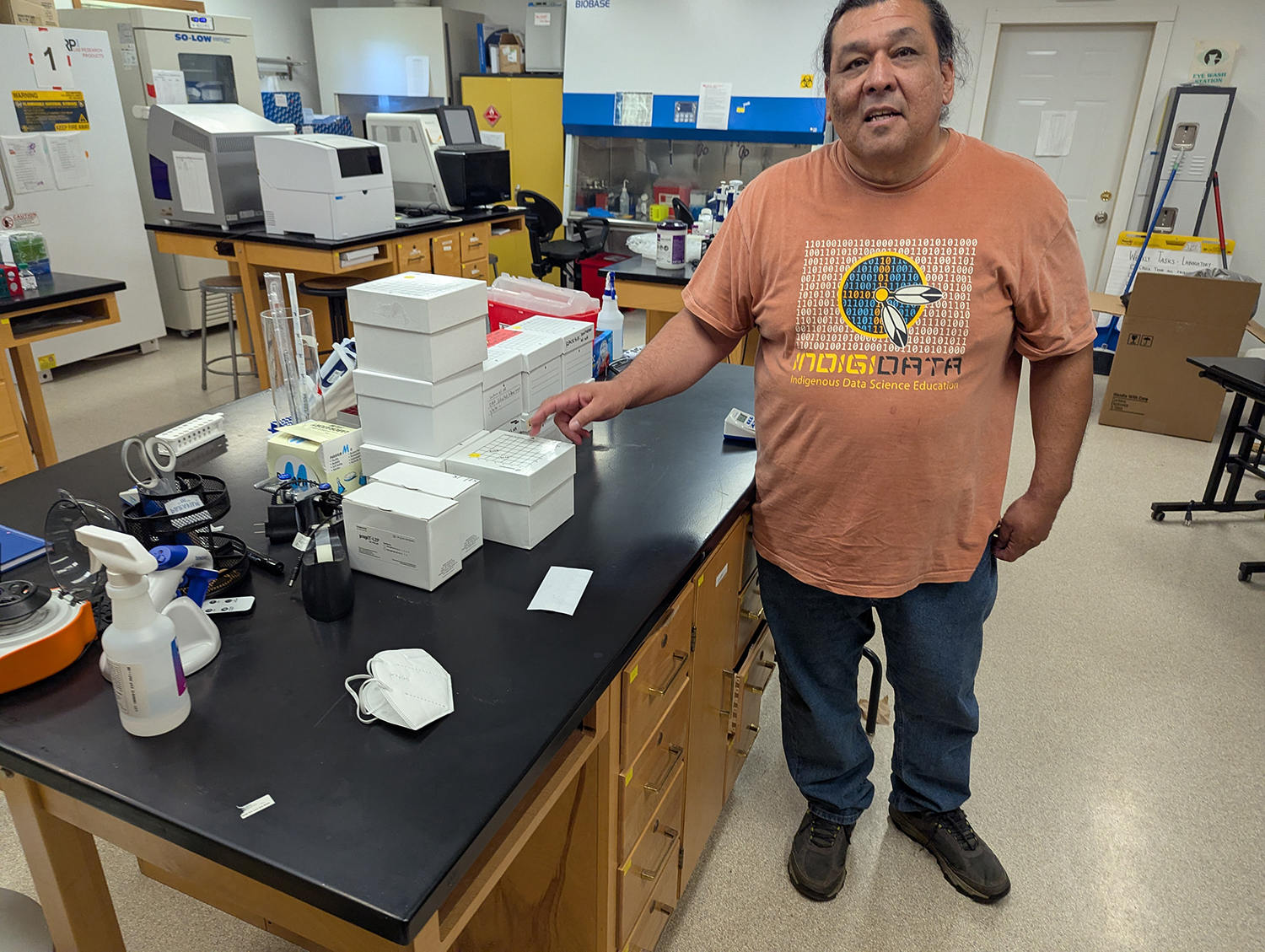

Testing equipment at the Native BioData Consortium laboratory in Eagle Buttle, South Dakota. (Photo by John Hult/South Dakota Searchlight)

Five tribes in South Dakota want their congressional delegation to help restore funding for a research project led in part by a South Dakota genetics lab.

The back-and-forth that’s played out over the past few weeks for the Data for Indigenous Implementations, Interventions, and Innovations Tribal Data Repository project is the latest twist in a funding tale that’s stretched across two presidential administrations and speaks to deep-seeded distrust — and attempts to address it — of the scientific community by Native American leaders.

At the center of those conversations is the Native BioData Consortium, a nonprofit science organization and laboratory based in Eagle Butte, on the Cheyenne River Reservation. It’s the data host and one of the lead agencies in the repository project, whose National Institutes of Health funding was cut short in March, alongside a host of other research projects related to COVID-19.

Leaders from the Oglala, Cheyenne River, Rosebud, Lower Brule and Standing Rock Sioux tribes in South Dakota each sent letters to U.S. Rep. Dusty Johnson’s office urging him to help reinstate funding for the repository.

The project was “collateral damage in a blanket cut to all COVID-19 research,” the letters say, but its goals and value were further-reaching.

The Eagle Butte lab got the largest share of the project’s $7 million in research funding, which was split among multiple teams scattered around the U.S. The lab’s team only used about a third of its approximately $3 million share before the funding was revoked this spring.

The repository project, the letters say, “is an innovative and very needed attempt to protect Tribal communities now and in all future pandemics, and also to create a bridge of diplomatic relationships with Tribes over biomedical, public health, environmental research data and beyond.”

The tribes’ letters were sent in tandem with a similar letter from the project’s leaders.

Tribal data repository concept

One of those leaders, Joseph Yracheta, is a co-founder and executive director of the Native BioData Consortium. His lab performs genetic testing and catalogs genetic data for tribal nations, leads genetics bootcamps for Native American students each year, and hopes to one day open a large-scale genetics facility and data center on Cheyenne River tribal land.

It’s also the data archive for the multi-state, multi-partner tribal data repository project. That project’s goals include the creation of a secure, Indigenous-led and centrally located database of tribal health and genetic information that would afford tribes the ability to control the flow and terms of use for their citizens’ data in scientific research.

Yracheta, who lives in Eagle Butte, is of P’urhépecha and Rarámurì descent, tribes located in areas now part of Mexico. His wife and children are members of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe.

In addition to Yracheta, the project’s leadership team comes from the University of California-Santa Cruz, Arizona State University, the University of Wisconsin, the University of Washington and Ohio State University.

The COVID-19 pandemic disproportionately affected tribal communities, but genetic data collection from tribal areas was spotty.

Yracheta told South Dakota Searchlight that reticence to share information was in part grounded in a wariness by tribal governments to share genetic data without assurances that it wouldn’t be replicated and reused for non-COVID research without their consent.

A dispute between the Havasupai Tribe in Arizona and the Arizona Board of Regents, Yracheta said, is one of the most often-cited reasons for that reticence. In the mid-1990s, the tribe gave DNA samples to Arizona State University researchers for a study on diabetes. In 2003, a member of the tribe attending the school learned the DNA samples had been used to study things like schizophrenia, inbreeding and migration theories, which the tribe hadn’t consented to. The tribe sued, and was eventually awarded $700,000.

The data repository work, Yracheta said, would create a trusted place for tribes to share their data without fear of it being used in ways tribal members wouldn’t want.

“All we want to do is be a safe harbor,” Yracheta said.

Paper outlines strategies for improved relations

According to a recently published research letter in the journal Nature, penned by the tribal data repository project’s leaders, the scientific community has largely embraced a framework for DNA data that expects it to be free, open, harmonized and easily replicable for research purposes.

Tribes, however, see problems with wholesale, unrestricted availability of DNA data. There are privacy concerns about mandated open data policies and concerns over the unrestricted use of data, the paper says. It cites the practice of private companies giving estimates of a person’s Native American ancestry that “undermine Tribal determinations of citizenship and override legally assured self-governance.”

“Decades of extractive and unethical practices have left Indigenous Peoples (distinct societies of Indigenous people) hesitant to engage with biomedical researchers despite remaining interested in biomedical advances,” the paper says.

There are also concerns that tribal genetic data would be used in the development of treatments that benefit primarily non-Native populations or generate profit the tribes wouldn’t see.

The solution, the paper posits, is a framework for data sharing that creates a common access point for data, but treats tribal nations as sovereign entities and requires consultation and consent for data use.

The database framework would be useful for COVID-19 research, the paper says, but could serve as a basis for a wide range of genetic data research projects.

Battle for funds

The repository’s federal funding didn’t come easy, Yracheta said, and was threatened before President Donald Trump’s administration deprioritized COVID-related research.

The money came through a competitive bidding process in a National Institutes of Health initiative meant to build a database of basic genetic information from Native Americans for use in COVID-19 research.

‘They saw the potential’: SDSU program boosts Native American success

The long application process included sparring with the NIH over the data ownership and access policies that would be attached to the finished product. The researchers were ultimately awarded $9 million in December of 2023 to create the repository and its associated protocols, including $2 million that went to Stanford University to serve as an administrator.

The repository work itself began in January of 2024, but Yracheta said the disputes with NIH leadership continued, in part over who would own the data and dictate its use. Within a few months of the funding announcement, the NIH shortened the project’s research timeline by a year and asked the team to wrap up by December 2025.

Since then, the tribal data repository team has set up the storage and access system into which biological information would flow. Among the work products are 82 contract templates and related documents tribes can use when approached for genetic data, and educational materials on their data sharing options through the secure repository system.

The team built model servers in Eagle Butte and Wisconsin and connected them to make sure there’s enough physical storage space to keep data safely out of the cloud, and developed a user interface to connect researchers with the contracts they’d need to sign with tribes to secure access to that data.

The next steps, Yracheta said, are to present the repository concept to tribes, convince leaders it’s a trustworthy place to share their information for the good of their own people and science as a whole, and to begin to fill it with data.

“We took the money and built the box, but we didn’t get to the important part, which was building those relationships,” Yracheta said.

In June, the group presented its materials to the NIH, but was told no further funding would be available, Yracheta said, as COVID-19 related research had largely ceased.

Plea for help to Rep. Johnson, response from Sen. Rounds

The letters to Rep. Johnson, sent a little over a week ago, asked his office to work for the funding’s reinstatement. They suggested that funding a database project would serve South Dakotans as the federal government works to encourage the expansion of data centers and its residents’ expertise in database design and management.

A spokeswoman for Johnson’s office, Kristen Blakely, told South Dakota Searchlight via email that the office is “looking into it and in contact with NIH to see why the grant was canceled.”

This week, Yracheta said, the team got some encouraging communication from the office of Sen. Mike Rounds, whose staff sent emails seeking more information about the history of the project’s funding.

Yracheta said the team hadn’t garnered any encouragement in its communications with South Dakota Republican Sen. John Thune. Neither senator got the letter sent to Johnson’s office. When asked about the letter by South Dakota Searchlight, Rounds spokeswoman Arden Koenecke said the senator had spoken about the repository in general terms with leaders of the Great Plains Tribal Leaders’ Health Board, but “didn’t get into specifics on cuts or locations.”

Rounds would be open to discussions on the issue, Koenecke said. Yracheta said the Rounds team contacted him this week.

Thune’s office did not respond to questions about the letter.

GET THE MORNING HEADLINES.